Michael Sailstorfer

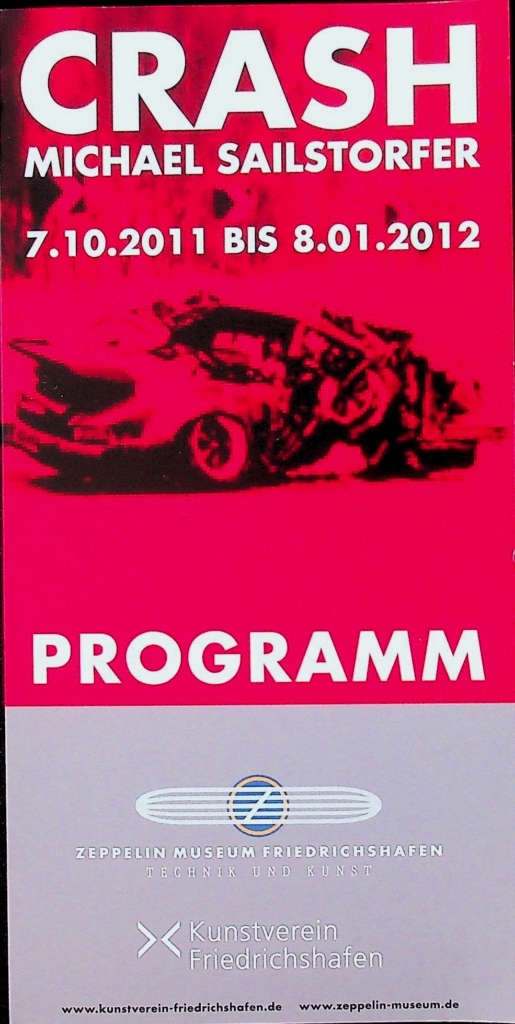

Crash

Anyone entering the exhibition space shares responsibility for what happens next. As a visitor, you step onto a stage that, through your mere presence, develops a dynamic all its own—unpredictable and uncontrollable. It’s no coincidence that the title of this work is Reaktor, a word that implies the full spectrum of dangers and threats we have been exposed to in the nuclear age—not only since Fukushima.

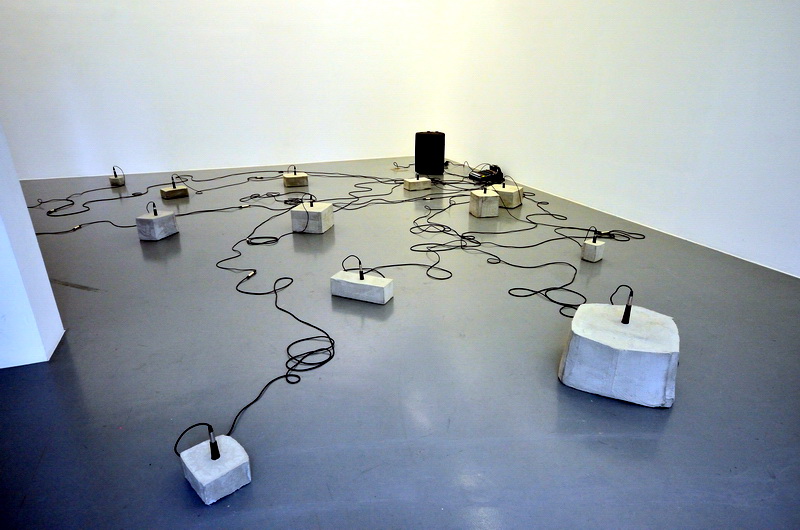

At first glance, we are faced with what appears to be a harmless collection of concrete blocks of various sizes, wired together and scattered across the floor. But in the very next moment, a humming or rumbling fills the room, vibrating in our stomachs and completely absorbing us. The source of this sound is easily explained: embedded in each cube is a microphone, connected to an active speaker. The concrete blocks pick up the vibrations of the floor, and when many people move through the space, the work amplifies the building’s vibrations. In other words, Sailstorfer’s Reaktor creates an acoustic image of an architectural space. The sculpture generates an audible representation of the room it occupies and simultaneously reflects the presence of its visitors.As the audience, we play a crucial role—we generate the sound. It is precisely this tension between space, installation, and viewer that matters to the artist. It raises the question of what sculpture can be—how it can expand and occupy far more space than what it physically takes up. At the same time, the body—our body—becomes part of the installation and thus of the space, in two ways: physically and acoustically. Through our movements and steps between the Reaktor blocks, which are projected into the room as sound, our bodies occupy far more space than would be possible physically alone.

This leads to the question: where do the boundaries lie—between artwork and space, artwork and viewer, viewer and space? In other words, we are dealing with a form of art that cannot be confined, and cannot be ignored, like a picture on the wall or a statue on a pedestal. Sailstorfer creates art that demands our full attenti

on and physically involves us—precisely because it incorporates objects from our everyday lives, our means of transportation, life itself, and thus also mortal danger.

On the upper level of the art association, another installation engages this same tension. Zeit ist keine Autobahn consists of a car tire mounted directly to the exhibition wall and driven by an electric motor. As the tire spins, it produces rubber dust that gradually accumulates on the floor over the course of the exhibition. Simultaneously, a strong tire smell spreads through the room, triggering a wide range of associations: car races, braking, speed—but also the danger posed by machines, the physical threat of injury from a wrong move or a careless touch. As viewers, we are confronted with this latent risk. The spinning tire, as a symbol of unstoppable progress and the power of technology, is revealed as an illusion and ultimately doomed to obsolescence—condemned to spin in place. Through this ceaseless movement on the wall, it is subject to wear and tear until it eventually destroys itself.

Time plays a key role in Sailstorfer’s work—not as a linear axis on which events unfold sequentially, but as a cycle in which we are inescapably embedded. The title Zeit ist keine Autobahn already suggests that this installation serves as a metaphor for a concept of time where we must reckon with stop signs, intersections, and dead ends. Smell and sound make us aware that even the exhibition space occupied by the installation undergoes changes over time—signs of wear, traces of odor—signs of life that extend beyond spatial boundaries and include us as the viewing public.So go ahead—embrace the experience! There is no actual danger to life, even if a work like Reaktor at times loudly demands our attention. After all, it is our own restlessness that is being held up to us like an acoustic mirror by this installation.

Curated by: Dr. Andrea Jahn