Xiaopeng Zhou

Swamping

So ein Haus mitten im Moor, ohne Nachbarschaft (abgesehen von einigen fremden Bauernhöfen), an keiner Straße gelegen und von keinem Menschen gefunden, ist eine gute Zuflucht, ein Ort, mit dem man bald durch ein unscheinbares Mimikry verschmilzt, und geeignet, nach vorwärts und nach rückwärts in Zukunft und Erinnerung ruhig und voll Gleichgewicht zu leben. (Rainer Maria Rilke an Franziska von Reventlow, 1901)

The poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke lends itself to explorations of a special kind. You don’t have to travel far and yet, if you do, you will reap great inner rewards – for Rilke is the poet of longing.In the monograph “Worpswede”, first published in 1903, the poet transforms the works of five Worpswede artists into linguistic paintings. Rilke conjures up an ode to the moorland landscape from descriptions of the paintings and biographies of the artists.The moor is no longer colourless and desolate. It is no longer horrible, but magnificent. And it is the ideal subject for painting.

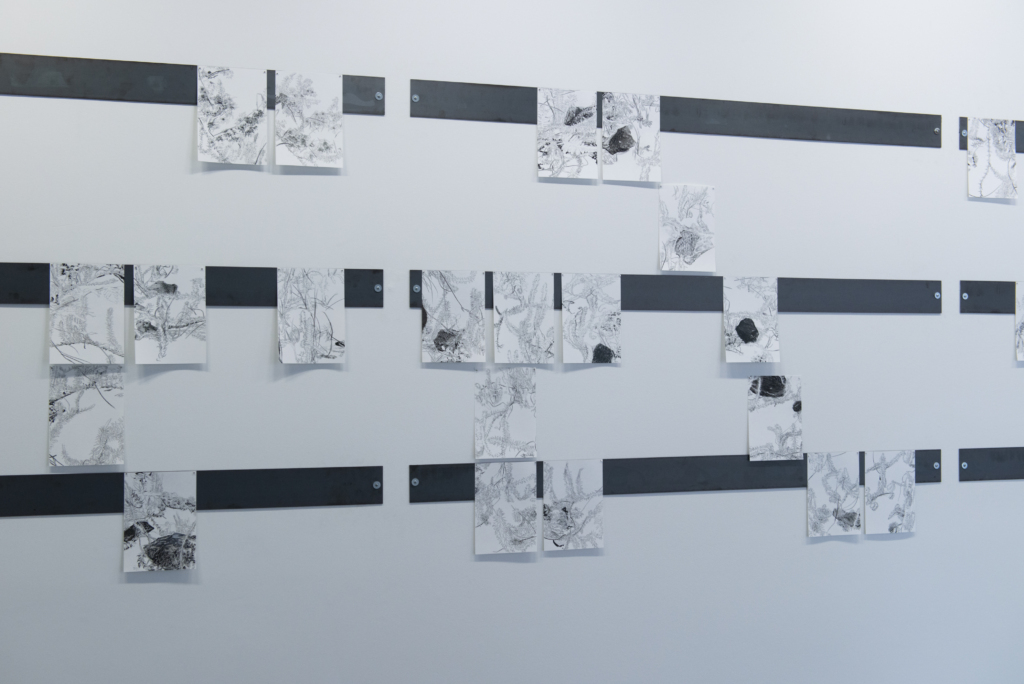

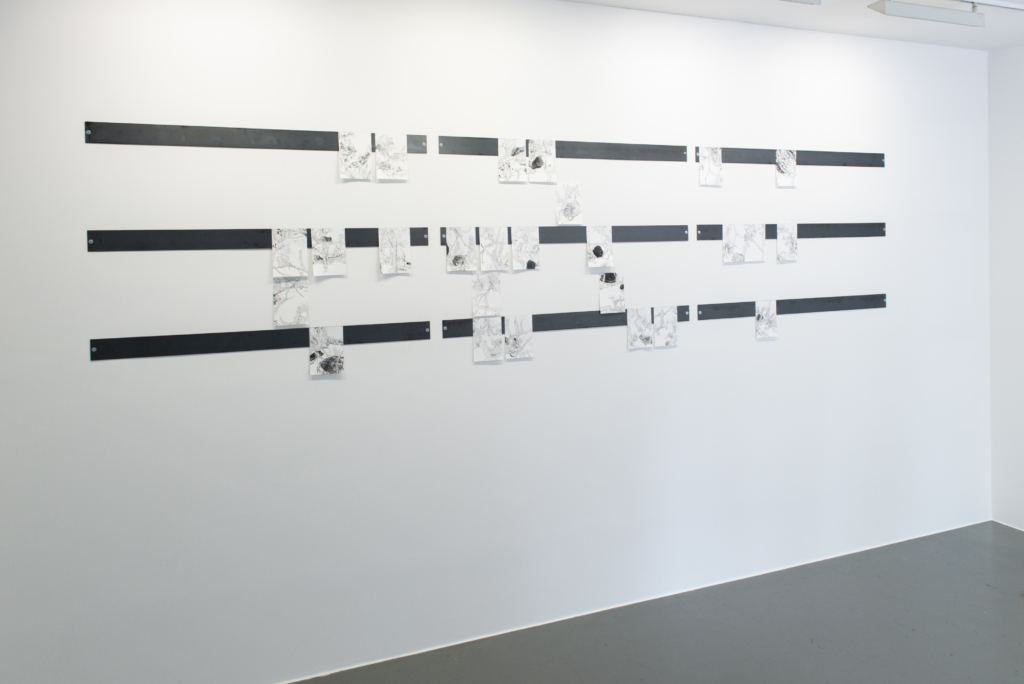

Xiaopeng Zhou’s exhibition swamping at Kunstverein Friedrichshafen evokes such a longing, a becoming one with the sometimes harsh landscape of the moor. For his solo exhibition, Zhou presents his long-standing interest in geology primarily in the form of drawings and installation elements. Fine strokes and shading run through his series of drawings. At first, it is a challenge to categorise the places and plants he is describing. Just as the moor oscillates between earth and water, between solid and liquid, so do the many seemingly simple drawings hanging in the exhibition space. Like Rilke’s poetry, the many perspectives and angles, but also the display and presentation of the works, invite a special form of exploration.

The swamp – an open and cultivated ecosystem, a barren landscape, desolate, rough, eerie. And also: the bog as a renaturation project and as a CO2-reducing hope to counteract climate change. Lycopodium is a species of plant native to the moor. Often referred to as ‘living fossils’, Lycopodium, as it is called in Latin, is an inconspicuous plant of 20 to 30 cm in height that grows on the forest floor or in wetlands where the artist has travelled to look for swamps (from the English word swamp, meaning bog or marshland). What makes Lycopodium special is that it has retained the structure of the first primeval plants, in which stems, leaves and roots are not clearly separated. Such features can be traced back more than 400 million years.

In the form of the drawn bear rag, Zhou’s graphic work combines documentary subtlety with an imagination that transcends transience. In his depictions, he combines traces of palaeontological scientific knowledge with autodidactic observations. In the casualness of his choice of motifs, his works evoke the forgotten, growth and decay, ageing and progress.

Some of the works presented were developed specifically for the site, for which Zhou travelled to the moors around Lake Constance. In doing so, he draws on regional ecological developments in southern Germany, which he was also able to gather through research at the Palaeontological Department of the Natural History Museum in Berlin. The exhibition therefore consists of two parts: a collection of black and white drawings on the ground floor and a relocation of artefacts, other objects and trays on the floor above.

In its concentration on the essential, Zhou’s drawing deliberately omits much. There is no background to the picture, these empty spaces are deliberately placed – nothing else is happening except a meticulous exploration of his chosen objects. These blank spaces can also be seen on the upper floor, faded traces of human sorting, suggesting research and categorisation rather than actual representation. This analysis and precision in Zhou’s work, the density of his subject matter, dissolves into the deliberate freedom of his motifs on white paper. The floors thus merge into a timeless depiction of this mystical place, the moor: it becomes a place where millennia merge, as Rilke said in 1901, “forwards and backwards in future and memory”.

Curated and with a text by: Marlene A. Schenk

[1] Johannes Heiner: Die Stille hinter den Worten des Dichters Rainer Maria Rilke, 2008.

[2] Fritz Mackensen, Otto Modersohn, Fritz Overbeck, Hans am Ende und Heinrich Vogeler.

[3] Rainer Maria Rilke: Worpswede. Monographie einer Landschaft und ihrer Maler, 2012.

[4] Günter Beyer: Eine Lange Nacht über das Moor. Es wankt und wuchert und schweigt, 2019.

Curator: Marlene A. Schenk